What does it mean to return home: following war, exile, a long absence, or after time itself has changed you?

We all have heard the famous idiom, "you can't go home again." This of course refers to the truism that once a person leaves a place, particularly his hometown or somewhere significant from his past, he cannot return to it in the same way he left. The phrase suggests that both the place and the person have changed, making it impossible to relive the past or experience it as it once was.

The ancient Greeks returned to this question again and again, giving rise to some of the most enduring stories of return, longing, and exile.

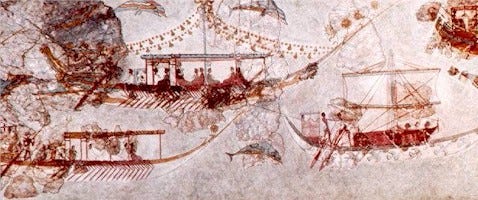

In classical literature there is a corpus of epic poetry known as the Epic Cycle, a collection of poems that complement Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey by narrating events that occurred before, during, and after the Trojan War. Some of these events are much better known than others, but all of them were well known to the Greeks of the Classical period and are necessary to fully understanding the events of the Trojan War.

Many famous stories, including that of the Trojan Horse and Achilles’ death from a poisoned arrow striking him in the heel are not included in The Iliad but are found in the poems of the Epic Cycle. These works include The Cypria, The Aethiopis, The Little Iliad, The Iliou Persis, The Nostoi, and The Telegony.

Sadly, these poems have not survived from antiquity and are only extant in summaries, quotations, and fragments.

Within the Epic Cycle there is a genre known as the nostoi (Νόστοι), or "Returns." The term nostoi refers both to a now-lost epic poem (Nostoi) and more broadly to a recurring theme in Greek mythology: the difficult return home after war.

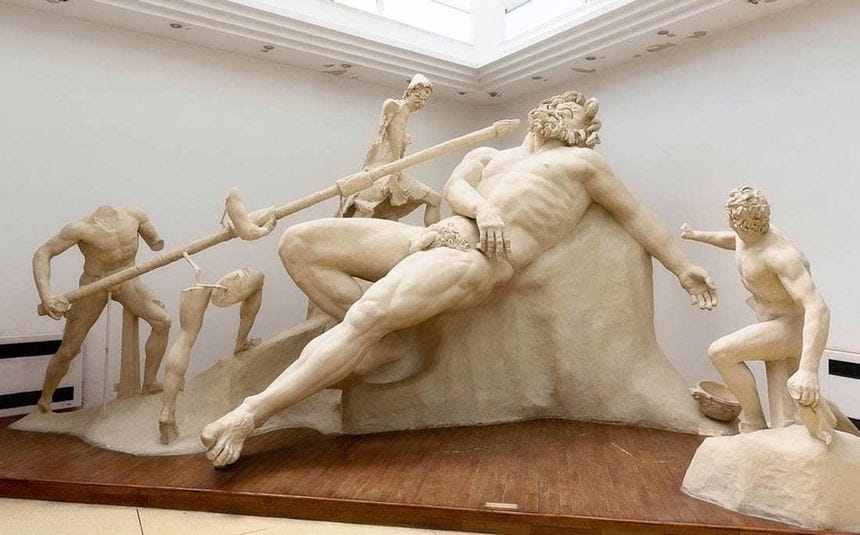

The story of Odysseus, as recounted in Homer’s Odyssey, is the most famous of the nostoi and follows the travails of the legendary hero on his return to Ithaca. Over the course of a ten-year journey he would face storms, monsters, and divine obstacles as recompense for having offended the gods. After blinding the Cyclops Polyphemus, Odysseus incurred the anger of Poseidon, who drove him off course time and again.

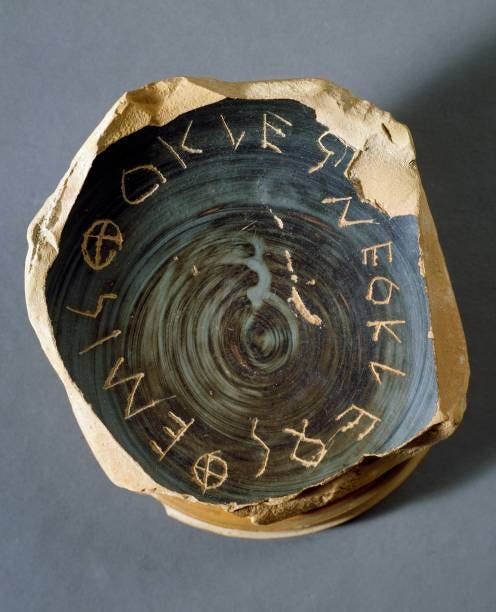

One of my favorite literary puns appears within this episode. After eating some of Odysseus’ men and drinking the Ithacans’ wine, Polyphemus asks Odysseus to tell him his name. Odysseus says, “Οὖτις ἐμοί γ᾽ ὄνομα.” (“Nobody is my name”). Later, after he has been blinded by Odysseus and is calling for help from his fellow Cyclopes, this exchange occurs:

"τίπτε τόσον, Πολύφημ᾽, ἀρημένος ὧδ᾽ ἐβόησας

νύκτα δι᾽ ἀμβροσίην καὶ ἀύπνους ἄμμε τίθησθα;

ἦ μή τίς σευ μῆλα βροτῶν ἀέκοντος ἐλαύνει;

ἦ μή τίς σ᾽ αὐτὸν κτείνει δόλῳ ἠὲ βίηφιν;"

τοὺς δ᾽ αὖτ᾽ ἐξ ἄντρου προσέφη κρατερὸς Πολύφημος:

"ὦ φίλοι, Οὖτίς με κτείνει δόλῳ οὐδὲ βίηφιν."“Why have you cried out so in distress, Polyphemus,

through the immortal night, and made us all sleepless?

Surely no mortal is driving off your flocks against your will?

Surely no one is killing you by force or trickery?”

Mighty Polyphemus called to them from inside the cave:

“Oh friends, Nobody is killing me with force and trickery.”1

Odysseus' clever use of a false name, “Nobody,” allows him to escape the island with his remaining men, as the other Cyclopes dismiss Polyphemus’ cries for help. After all, who would rush to stop “Nobody”?

There is a second pun in play as well. The repeated use of μή τίς (roughly “not this”) is associated with μῆτις, (“intelligence,”) leading to this exchange:

ὣς ἄρ᾽ ἔφαν ἀπιόντες, ἐμὸν δ᾽ ἐγέλασσε φίλον κῆρ,

ὡς ὄνομ᾽ ἐξαπάτησεν ἐμὸν καὶ μῆτις ἀμύμων.So [the Cyclopes] said as they went away, and I rejoiced in my heart,

that my name and my blameless intelligence fooled him.2

But true to form, Odysseus cannot resist the pull of glory. As he sails away, he reveals his true name, ensuring that Polyphemus can call down the wrath of his father, the god of the seas, and set in motion years of divine punishment.

Continuing on his journey, Odysseus would be blown off course with Ithaca in sight after his men open the bag of winds Aeolus had given him, face cannibals, shipwrecks, and the enchantress Circe, who turns his men into pigs. He would travel to the underworld and face trials by sea, encountering dangers such as the Sirens and the twin perils of Scylla and Charybdis. The surviving members of his crew, who had fought with him at Troy and braved the many dangers of the return journey, would perish after disobeying the gods, and Odysseus would then spend seven years captive on the island of the nymph Calypso before the gods finally allowed his release.

Finally washed ashore among the Phaeacians, he recounted his story and was at last returned to Ithaca, arriving alone and in disguise. There he found his home overrun with suitors and his son Telemachus, now grown into manhood, struggling to defend his mother and their household. In one final battle, using his legendary cunning and resolve, Odysseus and Telemachus would work together to reclaim their home. At last Odysseus would reunite with his faithful Penelope and restore order to the kingdom.

It is important to note when recounting this long ordeal that Odysseus never wanted to go to Troy in the first place, but had been forcibly compelled by others to join the war. In a story told in the Cypria, many years previously Odysseus had been a suitor to Helen and was therefore bound by the Oath of Tindareus, a binding pledge obligating him and the other suitors to support and protect the marriage of Helen and her chosen husband, Menelaus. Wanting to avoid joining the Greek expedition to Troy, Odysseus famously pretended to be insane by yoking a donkey and an ox to his plow and sowing salt into his fields. Calling his bluff, the Greek envoys placed his infant son Telemachus in front of the plow, causing Odysseus to swerve to avoid him, thereby revealing his sanity. This event would mark the beginning of Odysseus’ reluctant journey. That he never wished to go to Troy casts a long shadow over his story, framing his eventual homecoming not as a triumph, but as a restoration for a man who never wanted to leave home.

Interestingly enough, there is an alternative version of the Odysseus myth related by the Medieval Italian poet Dante Alighieri. In The Inferno, Ulysses (the Latinized form of Odysseus) is punished for the sin of fraudulent counsel. In this story Ulysses did not return to Ithaca but instead convinced his men to sail beyond the Pillars of Hercules, where they perished. Here, Odysseus becomes an anti-hero, rejecting the pull of family and home in favor of unbounded ambition and restless pursuit of adventure. Living in pre-Renaissance Italy, Dante almost certainly had never read Homer in the original Greek and was instead likely extrapolating from Roman interpretations found in Vergil, Ovid, and Cicero’s writings.

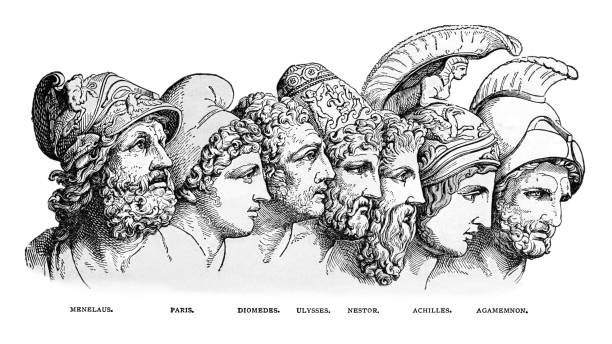

Other notable tales of the Greek heroes’ returns from Troy are included in the Nostoi, an epic poem originally composed in five books forming part of the Epic Cycle. It is unknown who wrote the Nostoi, although ancient writers variously attributed the poem to Agias of Troezen, Homer, and Eumelos of Corinth. Though now largely lost, the Nostoi recount the difficulties faced by Agamemnon, Menelaus, Diomedes, Nestor, and others as they attempted to return to their homes in Greece after the city’s destruction. Having angered the gods through acts of impiety and the desecration of temples during the sack of Troy, the Greeks were punished with long and perilous journeys home.

Agamemnon, the king of Mycenae and commander of the Greek forces at Troy, arrives home safely with the Trojan princess and prophetess Cassandra as his war prize, but his arrival is far from triumphant. He is soon murdered in his bath by his wife, Clytemnestra, and her lover, Aegisthus, in retribution for the sacrifice of their daughter Iphigenia before the war. This act of bloodshed sets in motion a cycle of vengeance and moral reckoning that unfolds in Aeschylus’ Oresteia.

Menelaus returns with his wife Helen but is blown off course and wanders for several years in Egypt and other lands before he is able to return to Sparta.

Diomedes, arguably the most warlike hero and wounder of gods, returns to Argos but finds that his wife has been unfaithful to him. He then leaves his home and sets sail for Magna Graecia in southern Italy.

Ajax the Lesser desecrates a temple of Athena by violently dragging Cassandra from its altar and is destroyed by Poseidon in retribution during his voyage home.

Only the elderly Nestor, the loquacious hero of Pylos, arrives home without incident. The Nostoi also recount the returns of other, lesser-known heroes whose stories fall outside the scope of this discussion.

For many the search for home is a primal motivation.

Odysseus, during his long captivity with the goddess Calypso remarks:

But in my heart I never gave consent.

Where shall a man find sweetness to surpass

his own home and his parents? In far lands

he shall not, though he find a house of gold.3

In the ancient world the place from which one hailed was among the most fundamental aspects of identity, along with family and status. A Greek was not simply a man; he was Athenian, Spartan, or Theban, his name and reputation anchored in his polis (“city”). Similarly, a Roman venerated his familia, (“family,”) gens, (“clan”), and citizenship status. To be exiled, as in the infamous punishment of ostracism meted out by the Athenian democracy to individuals like Thucydides or the imperial exile of the Romans, was not just to lose one’s home, but to lose part of one’s self.

The Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso, known to us as Ovid, complained bitterly of his exile to the Black Sea by the Emperor Augustus as the result of an indiscretion. Ovid wrote extensively about his exile in Tristia (“Sorrows”) and Epistulae ex Ponto (“Letters from the Black Sea”) but his complaints fell upon deaf ears.

Barbarus hic ego sum, qui non intellegor ulli.

“Here I am the barbarian, because no one understands me.” Trist. 5.10.37-38.

Roma, tibi patria est; cum quo periere parentes, / cumque tuum vixi, cumque sepultus ero.

“Rome, you are my fatherland; with you my parents died, with you I lived, and with you I shall be buried.” Epist. ex Ponto 2.9.11-12.

Quantum erat, o magni, morituro parcere, divi, / ut saltem patria contumularer humo?

“How little, great gods, to spare a dying man—just let me be buried in my native soil!” Trist. 3.3.1-2.

Quod patriae vultu vestroque caremus… utraque poena gravis; merui tamen urbe carere, / non merui tali forsitan esse loco.

“To be cut off from my country’s face and from yours, friends—each hurt is heavy; I may have earned banishment from the City, but not a place like this.” Trist. 5.10.47-50.

The dishonor of exile in the ancient world combined geographic dislocation with the threat of social erasure. Stripped of homeland and civic identity, the xenos in Greek or peregrinus in Latin was a foreigner without full political standing: being neither truly inside nor outside the community. In many respects, such a figure resembled the slave: a person severed from homeland, ancestry, and independent legal personhood. The Latin word for slave, servus, is commonly believed to be etymologically linked to servare, meaning “to save” or “to preserve,” a reference to the early practice in warfare whereby captives who surrendered were “saved” from death but lived on in bondage. Upon manumission, Roman slaves would undergo formal civic rituals and take on the name (nomen) of their former master, symbolically entering his familia and gaining a tenuous form of social reintegration.

Returning to Dante, the Italian poet was also an exile, having been banished from his native Florence on pain of death in 1302 as the result of intense political infighting between rival factions. He spent the rest of his life in various cities, hoping to return to Florence. He died in Ravenna in 1321, his longing to return unfulfilled. Famously, he has his ancestor Cacciaguida foretell his exile in Paradiso:

“You shall leave everything you love most dearly:

this is the arrow that the bow of exile

shoots first. You will know how salty is

the taste of another man’s bread, and how hard

a path it is to go down and up

another man’s stairs.”

In this world, nostos was more than a homecoming; it was a restoration of selfhood and reintegration into established society.

Even though the nostoi of the Epic Cycle largely survive only in fragments, the concern at their core still speaks to us: how do we return after we’ve been changed? And what do we do when the place we return to no longer feels like home?

Many of us feel a similar ache today. We live with a sense not just of dislocation, but of estrangement: from community, from continuity, and from the world as it should be. We, like the exiles Ovid and Dante, feel like strangers in a strange land, longing for a restoration of our sense of place and belonging.

The Odyssey may end with Odysseus reclaiming his home, but the deeper truth of nostos is that returning is never as simple as stepping through the door. What happens when the world has changed, and so have you? In the next part, I’ll explore further how exile, identity, and belonging shaped the ancient imagination and why the question of home still haunts us today.

9.360-408 | Dickinson College Commentaries

Ibid.

Odyssey 9.28–31 (trans. Robert Fitzgerald)